My life is not a day at the beach (no, literally)

On chronic illness, grief, and accepting reality... inland

This morning, just before I woke, I had yet another dream that I was at “Burning Man.”

Some impressionistic fantasy version of the festival has been the setting of my dreams (usually anxiety dreams, but not always) since I first attended the real festival in 2002.

But every new dream, for more than 20 years now, has its own specific aesthetic, flavor, and message.

In this version, Burning Man was a vast, varied landscape, with hills, valleys, and some kind of body of water.

I was camped by myself, all my belongings contained inside my car and a van, a feeling of both security and scarcity attached to my stark, unadorned little set-up.

And next to me was a friend I know from that world: a vibrant, wealthy woman with a big, vibrant, happy family who always party together. Their camp was colorful and crowded and lush and abundant. Overflowing with people and RVs and shade and seating and costume racks and art cars upholstered with fun fur.

Our two camps stood alone atop a bald, bare hill, overlooking the heart of the festival, which was a small trek away. I had the sense that it was a big effort to get there for me, less so for her/them. Her crew were often in and out, coming and going. Me, not so much. I could either stay home or go out, but not flit between. Either decision was a long-term commitment. “I would be able to enjoy this more if I could do it like they do, if I had what they had,” I thought.

Suddenly, the sky exploded with fireworks. Gorgeous, bright, panoramic, filling the whole horizon at once, 10 or 20 bursts together, continuously, for a long time. I gasped. How beautiful, I thought. How magical that I am here in this moment to see this. But I was also sad. All this wonder, I thought. And no one to share it with.

I contemplated leaving. This was so much work, and so lonely. Maybe not worth the reward.

But as I turned around, my car had been stolen, along with everything I owned. Festival cops soon found and returned it, but now everything inside was broken, dirty, violated, ruined. My camp had been bare bones before, but now I had even less… comfort? resources? safety net? bandwidth? Leaving was no longer a choice. I couldn’t even stay if I wanted to.

When I finally woke up, the first thing I did was cry.

Well, first I recorded my HRV with my Apple Watch, then went to the bathroom, then checked my text messages, then did my 20-minute vagus nerve meditation, and then I cried.

It wasn’t about the dream.

It was about my day.

And about my headache.

Today I was supposed to see my sister at the beach.

She has been visiting California from Montana since early last month, and moved from her tiny house rental down the block from me to a beachfront AirBnB a few weeks ago. Which is how long I’ve been trying to gather the energy to visit her there.

Her spot is in the next town over, a 20-minute drive each way if there’s no traffic. Which doesn’t seem like a big deal, if you’re a normie (read: able-bodied).

But I’m no normie. Thanks to my severe ME/CFS, I haven’t left my house at all since 2018, except for one terrifying fire evacuation and the handful of medical appointments per year that can’t be done over telehealth (turns out they don’t have the tech yet to squish your boobs over Zoom). When I do go out, my destination is almost always within a 5 mile radius of my bed.

So for me, a 40-minute round trip is a very big deal.

The reason for my Rapunzel life is multifold. There are, of course, all the ways leaving the house is exhausting or hard on my system: stairs, noise, human interaction, sitting upright, smells, allergens. And there are the ways it’s now dangerous: COVID, RSV, norovirus, measles?!?!? TUBERCULOSIS?!?!? - all of which could reduce my already dismal quality of life, at best, or kick me into an even lower bracket of severe illness, at worst. (Well, I guess death is even worse than that… maybe. You should see our suicide rates...it’s rough out here.) But neither of those are the biggest reason I’m housebound.

The biggest reason is that my energy envelope is so small that by the time I factor in the effort and time of leaving my house, and then returning to it, there is so little time in between, it’s hardly worth the effort (and the days it will take me to recover from it).

On any given day, I can engage in a small number of activities (e.g. writing, a Zoom, a visit, a phone call, watching TV, doing dishes) for a small number of minutes (around 20 to 40 depending on the day) without paying for it for days, as long as I rest immediately before and after doing it.

But increase the time beyond 40 minutes, and I am guaranteed to pay for it, no matter how much I rest. (Though how much I rest will determine how long I pay for it and how bad the payback feels. The spectrum goes from A: sleepier than normal, a little headache-y, can’t do much but nap and watch TV but this is bearable, to Z: OMG EVERYTHING HURTS I WANT TO DIE AND ALSO WHY CAN’T I STOP CRYING.)

And so even if I were in a wheelchair, even if someone picked me up and dropped me off, even if the place I went was calm and peaceful and lovely and the people there were accommodating and never ever ever chewing gum or wearing perfume, I’d still only have half a network sitcom’s amount of time at most to enjoy it before I turned into a pumpkin. And that’s hardly enough time to put your coat down and move past chatting about the weather.

Or I can try to stay long enough to enjoy it, and then feel like shit for days or weeks afterwards, which, no matter how fun it is, rarely truly feels worth it.

So usually I don’t even bother.

But every once in a while something comes along that makes me want to take the risk, or tricks me into thinking maybe this time the risk won’t be so high.

And this spring, that thing was visiting my sister at the beach.

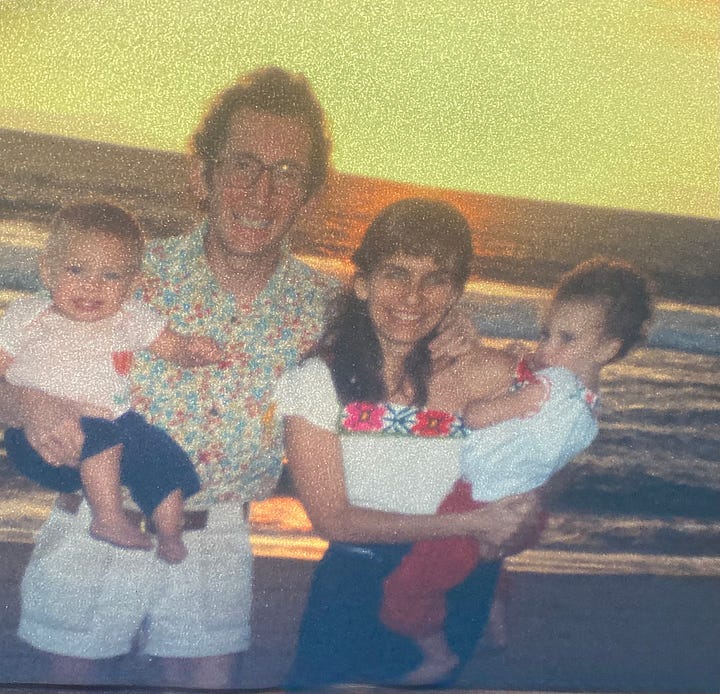

My sister and I both have a special relationship to the beach.

We were born and raised at Silver Strand, a tiny, funky neighborhood with a locals-only surf spot, a punk scene that spawned the genre Nardcore, and soon-to-be-but-not-quite-yet million dollar houses built right on the sand.

My dad, a young Jewish doctor from Long Island with dreams of waking to the sound of seagulls and hosting July 4 parties with live bands, built one of those homes from scratch, right on Ocean Drive, back when there were still empty lots (and houses were still made entirely out of dark brown shingles, and all the wind guards on balconies were still tinted blue).

I didn’t always like the overcast weather or sand in my sheets, and we moved before I was old enough to appreciate easy access to tanning, sneaking out, or surfer boys. But something in my bones registered “Beach” as “Home,” and I would return to the beach, and to Silver Strand, over and over throughout my life, for comfort and spiritual connection. And so would my sister.

When I was 23, fresh out of eating disorder treatment and so emotionally raw, a friend and I rented a house mere blocks from my childhood home, and I’d walk my now-dead dad’s beach every morning before work. Twenty years later, in another moment of spiritual and emotional realignment, I moved to Venice Beach, and spent many an evening on a sunset-colored Moroccan blanket, meditating and praying to the waves.

And last year, my sister, upon her first visit home since COVID, since getting cancer, since being diagnosed with our dad’s scary muscle disease, since her ME/CFS got worse, also sought the beach. She rented a little cottage right there on the sand, a few blocks from where she used to run around naked in the living room while our dad blasted The Beach Boys from his state-of-the-art speakers.

And despite my limitations, I decided to meet her there.

I drove myself the 20 long miles, blissfully alone in a car for the first time in forever, blasting Pearl Jam and Tom Petty on the Oldies radio station (!?!?!) and feeling on so many levels like a teenager who just got her license.

I marveled gleefully, almost tearfully, at the mundane landmarks I’ve driven past my whole life but hadn’t laid eyes on in half a decade despite living so close: the row of auto shops along the side of the 101 as you approach Rice and Rose: the long stretch of wild and then agricultural fields as you move south on Victoria from Ventura to Oxnard: the shimmering eucalyptus trees that herald the approach to Channel Islands: the miniature Fisherman’s Wharf at the entrance to the Silver Strand enclave; Kiddie Beach; the corner store; Pepe’s burrito stand; and finally, our street. Ocean Drive, where every driveway has sideburns made of sand.

I arrived happy and full, if already starting to run out of steam.

And what happened next was so beautiful, I have since turned it into a meditation. The practice is part of a program I’m in that asks me to recall happy memories in great detail, in order to induce a feeling of joy and flood my body with stress-reducing, nervous system-regulating chemicals, and to do it over and over and over so that the neural pathways become so strong, that, in times of distress, all it takes is a keyword to trigger the same body response. The idea is to use those memories as buoys. As lighthouses. As balloons to lift me up during dark moments, not to spiritually bypass them, but to help buffer me through them. A boat and a life jacket in white water.

And of the several memories I use as my go-tos, my favorite and most effective is the memory of that day:

My sister and I lounging together on the couch, our legs touching, me studying her eyes, her new bangs, above her mask.

The warm, bright room with the giant windows, the fresh breeze blowing in through the open doors.

The texture of sun-bleached wood under bare feet as I walk out to the deck.

Big big blue sky stretching out forever.

Big big blue ocean stretching out forever.

Long, narrow strip of bleached sand stretching right, towards the jetty, the bathrooms, the parking lot.

Stretching left, towards the graffiti wall and the shipwrecked luxury liner.

A robin’s egg blue lifeguard stand directly in front of us, right out of a “California” postcard.

Other beach houses - tall modern boxes made of glass and concrete, charming little bungalows made of wood and wind chimes - all crowded up close on each side, shoulder to shoulder to shoulder.

Short fences and outcrops of ice plant. Adirondack chairs and plastic beach toys and striped towels, all just out, visible from one person’s patio to the next.

My sister and I, stepping off the deck into the sand. Not far, just far enough to feel the shimmering eponymous grains between our toes, fine as flour, streaked with glittering black tar.

Painting semi-circles with my toes. Wiggling my feet until I’m buried up to my ankles. Smoothing flat planes like my soles are Zambonis, and then trying to stand upon them with weight evenly distributed, so as not to break the surface.

Feeling expansive looking out at sea and sky. Feeling simultaneously contained by the houses, by the jetty and the wall. Protected. Safe. Connected to my sister.

Thinking I am home. But also I am alive and I am in the world!

… And this is the part where I end the meditation.

Because next, I feel tired. Very tired.

We rinse our feet and go inside, and I become increasingly spacy as my body battery runs out, until I finally drag myself into the car and drive home, nearly crashing at least once out of sheer exhaustion and brain fog (and no, this was neither safe nor smart).

After that visit, it took me weeks to recover. There was no doubt it had been too much. Too far. Too hard. Not to be repeated.

But it had also been GLORIOUS.

Now, all I have to say in my head is the keywords “feet in the sand with Sally” and I smile involuntarily, my lungs expand and take in more air, my heart rate slows. I suddenly remember I am not just a head floating in space, but I also have a body, with a spine, a belly, a pelvic floor, tingling feet. It is magic.

And so even though the aftermath of that trip was hard on me, when I started doing paint by numbers soon after, I chose a painting that looks like Silver Strand (that, by no coincidence, is one my sister was also painting while she was here), and I hung the finished painting on the wall across from the foot of my bed.

Though the visit hurt me then, its memory seems to be part of what is healing me now.

That healing work is part of why I have seen some improvement this year, after years of little to no movement in that regard.

And it’s part of what gave me so much hope that this year’s visit might not be too much - at least, not as much as last year’s.

During those weeks my sister was nearby and coming to my house almost daily, we were both astonished and heartened by how much I’d changed since last year. I was more present and energetic. I was loose and easeful in my body. The time I could spend in her presence ballooned from an hour to four, or sometimes, if we napped together too, even six. I wiggled in my chair and sang along to Alanis Morissette. Instead of me always being the one needing caretaking, I was able to help her when she was having a bad day - to get her food, to grab her a pillow.

None of that was possible a year ago.

Everything seemed possible now. A beach visit least of all.

And so my optimism bloomed.

When she left for her new digs, I figured I’d see her at least once, if not multiple times, if not staying over for a night, a week… more? I planned my first trip for later that week.

But the brutal crash that hit days after her departure (like clockwork), was sobering. The pain. The fatigue. The TEARS. SO MANY TEARS. The hopelessness and despair.

By the end of the week, I was still in the hole. A trip was clearly impossible.

But she still had a few more weeks in her cute little apartment. We had time.

So time passed. And passed. I emerged from the crash, but I felt shaky. I’d climbed back up the ladder, but the rung I’d reached wasn’t as high as the one I’d fallen from. The optimism and hope and resilience I’d felt just weeks before now felt misty and elusive. I was scared. I didn’t want to risk falling back into the hole, or into an even deeper one. So I waited to feel more solid.

But as I waited, the window began to close. Last Monday, we started the clock on her final week. And though I still felt unsteady and unsure, I concluded that I would visit, no matter what, as long as my energy allowed it. Fear wouldn’t keep me away. Only symptoms. Only reality.

So Sunday, today, her very last day, would be the day.

Yesterday, when I woke up, I didn’t feel well. Headachey and anxious, sore throat and sore muscles… not a good sign.

But I started planning anyway. Choosing outfits, making packing lists, nailing down transportation options. Pulling tarot cards for every possible configuration of timing and masking.

Something in me felt like it wasn’t all quite real, that it might not happen, that I might not be up for it, but I was unbothered… mostly.

As I snuggled into bed, before falling asleep, I whispered a quick prayer to whoever it is who collects them: may I wake up either excited and happy to go, or clear that I must stay home. I felt confident that whichever it was, I would feel fine.

But I forgot to add “clear and happy to stay home.”

And so when I woke this morning from my dream, I did not feel fine.

I did not feel excited to go, and I did feel clear: A pulsing headache stretched tight across my brow and throbbed behind my left eye. I dragged myself to the bathroom with what felt like great effort, imagining how much more effort it would take to descend my stairs, to walk in sand, to hold a conversation, to adjust to a new place, to access the discipline required to rest when I needed them. It all felt like a lot. It was already going to be a push. But now it felt like too much push. Impossible push.

And then my transportation plans fell through. If I were to go, I’d have to go much earlier than planned, and either leave sooner or much much later than worked for my body.

It was the final straw.

It was definitely too much.

Even if a new transportation solution could be found, I didn’t feel emotionally capable of adjusting to a new arrangement. Which itself was proof that it was all too much. If I wasn’t resilient enough for a simple change of plans, I wasn’t resilient enough for the visit at all.

And that’s when I cried.

Big, wet tears, and those sobs that feel like they originate from inside your heart, as though the muscle is trying to push the pain right through your sternum and out of your chest.

This wasn’t just disappointment.

This was capital “G” Grief.

This disease, this existence, involves so much grief that it’s impossible to process it all in real time. I spent nearly two years, before my diagnosis but after moving in with my parents, consumed with such intense depression I thought it might literally kill me. And as I’ve grown further and further away from that time and place, sometimes the sadness feels so far away that I think it isn’t even there anymore.

But it is.

It is always there.

Chronic illness is a state of continuous grief. About what is versus what you wish could be. About what isn’t fair (getting sick at all, living in an ableist world, illness that would’ve been preventable if only someone - the government, a doctor, your parents - had caught something or done something sooner). About what you’ve missed and are missing and will continue to miss. The hobbies and passions and careers you can’t do. The places you can’t go. How you wish you could show up for people you love, but can’t. How you wish you could allow them to show up for you, but can’t.

You can’t live in a state of constant grief, and so most of us find a way not to. But the grief has to go somewhere, and so it collects. It pools. It gathers in underground springs, and every once in a while, the grief bubbles - or geysers - to the surface and demands to be felt.

And today was one of those days.

I called my sister on FaceTime to give her the news, to talk it through, to seek comfort. As soon as I saw her face, already exuding knowing and compassion, I crumpled again.

“I don’t feel good,” I wept. “And I’m saaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaad.”

And then I wept some more. And more. And more. And she just held me, in that space, and let me. And as the tears came, all the reasons for the tears became clearer.

Yes I was sad I wouldn’t see her, but I would do that in a day or two anyway, when she returned to a rental in my town. Yes, I was sad about disappointing her, of making her feel bad, about her maybe being mad at me, about maybe ruining our relationship FOREVERRRR (all of which she reassured me weren’t happening). Yes I was sad I couldn’t see the beach again, put my feet in the sand again, feel that infinite sky again, share that experience with her again. Record another joyful memory that I could then replay on a loop for the coming year again.

But those weren’t even really it.

Most of all, I was sad about reality. My reality.

I was sad that, no matter how hard I tried, I could not make my body capable of doing more than it could do.

No matter how much I wanted it, I could not make the trip easier than it was.

No matter how optimistic I’d felt last month, no matter how much better I’m doing than last year, how much better my sister and I are at resting together, I could not change the fact that I am sick and I have limits and sometimes I simply cannot do or have what I want or need. Neither of us can.

And that is when I remembered my dream.

“I could enjoy this more if I could do it like they do, if I had what they had,” I remembered thinking.

And then I thought about all the people like my dream neighbors. Who can go to the beach, can drive 40 minutes in one day, can make a plan on a Wednesday to do something on a Sunday and nearly guarantee they’ll be able to follow through with that plan.

I remembered seeing those beautiful dream fireworks, in appreciative awe but also lonely, and thought of myself staying home alone in my apartment today, painting and writing and appreciating my stunning view of the Santa Monica Mountains, but in solitude.

I remembered deciding to leave the festival because it was too much work, and my chance of enjoying it like my neighbors could was impossible, and then being sent home limping with my broken stolen car, even less resourced than I was before, and then it felt like a warning and a prophecy.

Duh, I thought.

My dream was about today.

My dream was about my life.

My dream was about acknowledging and accepting reality. That some people have the resources to do and enjoy things that I do not have the resources - physical, emotional, mental, financial, or sociopolitical - to do and enjoy. That we can look like we’re the same, we can be in the same place, doing the same thing, looking out at the same vista, have the same amount of ground to cover, but we are not the same.

That there can still be beauty in that life. But there is also sadness. There is also loss.

And sometimes there is nothing to be done about it except see it. Greet it. Feel it. And then do what needs doing.

In the dream, what needed doing was leaving.

In real life, what needed doing was staying.

And so after half an hour of weeping and processing and finding solace with my sister, I got off the phone. I got out of bed and put on my comfiest sweats. I made myself breakfast. I sat at my dining room table and let dark chocolate melt on my tongue as I looked out at my pretty view. I settled in. I took care of myself. I went on with my day.

And a few hours later, I laid down for my first of my daily naps. I climbed onto my adjustable bed, slipped my feet into the pneumatic leg compression device that helps pump my sluggish blood to my thirsty brain, adjusted the headphones that protect me from the assault of traffic noise and leaf blowers, and caught a glimpse of the beach painting on the wall, just before I closed my eyes.

“Feet in the sand with Sally,” I thought, a little melancholy this time, but it still worked. I still felt the warm wash of joy and calm and peace and connection through my whole body.

“Maybe next year,” I thought too.

And then I fell asleep, daring to dream again.

thank you so much for sharing your beautiful, heartbreaking reality

Always so good. I'm so glad you're writing. I know the feelings in this one by heart.