Eight years.

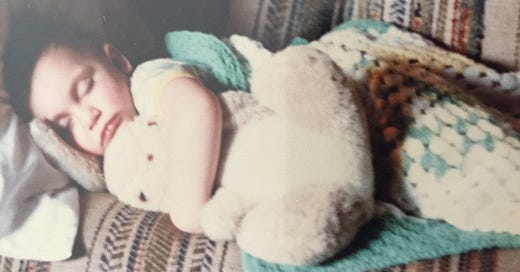

I have been in bed for eight years.

I have been in bed for the length of both high school and college combined. If this phase of my illness were a child, it would be in third grade. If it were a president, it would be finishing out its second term.

I have been in bed longer than Lost, Mad Men, The Sopranos, The West Wing, and Buffy the Vampire Slayer were on TV.

In two years, I will have been in bed for a full decade.

I realized this the other day while lying flat on a massage table in my living room, the base of my skull cradled in the hands of my new craniosacral therapist. She comes to me because I am too sick to go to her.

“I feel a buzzing,” she said, through the N-95 I gave her. “Like trapped energy. How long have you been in bed, again?”

Part of me wanted to say “not long,” because in a way, that feels true. My friend says chronic illness is a form of time travel, and I certainly experience it that way. Time slows down, time speeds up… one moment I’m living in the future afraid of what might come, the next I’m living in the past missing - or tortured by - what has been. Jumping through time, across tesseracts, lying in a hospital bed having surgery on my eye and then suddenly my body tenses and it thinks I am in the hospital bed where I thought I would die six years ago.

Time is liquid. Amorphous. Days are oceans. Years are dew drops.

This moment, there on the table with my head in the little basket the therapist made with her hands, listening to the birds chirp through my open windows and the air purifier whir like a rushing river, time had slowed down.

I was Being Here Now. I didn’t have an immediate answer for her, because What Even is Time, but also I didn’t know.

When your days are the same, day after day after day after day, meds nap eat meds nap eat meds text text TV text meds nap eat meds text internet TV sleep wake up ONCE MORE WITH FEELING, always in the same place, never leaving the house, always alone, living in a climate where seasonal changes are subtle, it is sometimes hard to notice time passing. To distinguish one year from the other.

And no kids to be getting taller, learning new things. No partners to be coming or going. Not even any pets to be getting older and slower. The only other living thing in my space, besides the ants, the carpet beetles, and the spiders I occasionally talk to, is a ficus, and he pretty much looks the same as the day my friend brought him over to me in 2019.

Even my Christmas tree - fake - is suspended in time.

So it feels as much like I’ve been living in this apartment forever as it does that I just moved in last year.

But as I contemplated her question, I did the math.

2016 was the last year of life as I knew it. I was living in Venice Beach, working at a spiritual bookstore, sure I was going to cure my “mysterious” illness with crystals and manifestation. That’s the year things finally took the last turn, thanks to the combined effects of a Soul Cycle class I knew I shouldn’t take that left me feeling poisoned, a trip to see my favorite bands at Chicago Riot Fest which was glorious but also well beyond my limits, the emotional devastation of being unable to stay in my dream house (because my mean old landlords insisted on, you know, me paying them rent, and one can only pay rent if one can actually work), and the physical impact of moving out of that house mostly by myself in one final manic, OCD-and-wine-fueled push that robbed my body of its last remaining energy… seemingly forever.

I spent the last month of 2016 in an art residency at my friend’s arts complex in Santa Barbara, trying to work on what was then a screenplay and also somehow feel better by following the rules of the book “The Power of When,” which meant never sleeping except at night, and never lying in bed except when sleeping. And so I spent that month laying on the hard little couch, too sick and fatigued to write, but trying not to doze off. Sometimes driving to a bookstore or the farmers market to get out of the house, only to feel so sick I’d sleep for an hour in the parking lot and then drive home again, never having gotten out of the car.

By January 2017, I moved back in with my parents. “Temporarily.” “To find a job.” “To get my shit together.” Except I spent the first several months of that year in bed with a “flu” that wouldn’t go away. I spent the rest of the year pinging and ponging between doctors who might help diagnose the strange then-unnamed (and sometimes mis-named) illness that has plagued me since I was 17, and trying to solve whatever psychological problem I was certain was making me so lazy and unmotivated and incapable of just putting my head down and doing life like everyone else.

By 2018, we were all starting to believe that I was actually truly sick. We fired the “business coach” who was helping me with my issues with getting a job because it turns out my issues with getting a job were that I couldn't stay upright long enough to work. I was despairing and depressed, never planning to kill myself but often fantasizing that I could – or could at least drink NyQuil every time I woke up until this phase of my life was over.

My mom encouraged me to visit friends to fend off the depression, so I did – Belle and Hank and Alex and Camille and Alison in San Francisco, Alicia in Vacaville, Laurie’s 40th in Philly, Katy’s 40th in the Central Valley, my own 40th in L.A. But all I could do once I got there was lie in bed all day. And though I felt a little better while there, likely fueled by adrenaline and novelty, I felt much worse every time I got home.

It was August of that year, in a tiny office in a suburb outside Salt Lake City, after literal days of intake exams and interviews and tests, that I finally got my diagnosis: Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS), and heard the words so validating they made me weep: “You are very, very sick.”

2019, I started therapy for the first time since my 20s, and began to accept my new life as a disabled, chronically ill middle-aged woman. My parents began to accept I was likely never leaving their house again.

2020, COVID. The world suddenly living like I already did. A brief moment of feeling a part of the collective experience again. And then, my sister got cancer.

2021, my parents go to Montana to help my sister through chemo. I am devastated I am too sick to join them. I stay home alone, save from a visit from Belle, and learn that having no help is terrifying, but being alone gives me room to breathe, and feel like an adult. My sister goes into remission, my parents return, and we all agree I need my own space. We find my apartment, with its upside down electrical outlets and its gorgeous view of the mountains. I move in.

2022, I live here.

2023, I live here.

2024, I live here.

And okay, yes, things did happen in those three years. I joined a writing class. The screenplay became a memoir. I made multiple new friends. My sister came to visit, marking the first time in four years we shared space, hugged each other, giggled IRL. There was the hurriquake. I got cataracts. I changed doctors. A couple times a year, friends or family visited. I got a new chair.

But all of that feels like it could’ve happened the same year. In fact, this New Year’s Eve is the first in a long time I felt like the page on the calendar was actually flipping forward, that it didn’t feel awkward to write “2025” in my journal instead of “2024,” because for whatever reason, this is the first year in awhile that feels like a different unit of time than the last few Decembers that just slid or melted into seemingly the same Januarys.

And so while I wasn’t looking, eight years have passed.

Or while I was looking intently and intensely everywhere but at the time that was passing: at my childhood trauma, at my new OCD diagnosis, at my symptoms and what to do about them, at my phone inside which all my friends live. With no real goals or deadlines to meet, and only the occasional milestone (turning 45 was a moment that time felt like time), barely able to celebrate holidays, and having mostly given up on the idea of a future (but not in a way that’s as depressing as that sounds), the passage of time hardly seems to matter.

And yet.

Eight is quite a lot.

It’s especially a lot for everyone else.

While I have been living the same year for four years, parked in a metaphorical lounge chair next to a metaphorical escalator, the people around me have been riding up and up and up and up, waving to me as they go. Having children. Getting promotions. Running marathons. Climbing mountains. Getting dogs. Getting old.

I don’t really know what to make of this.

I know I should be sad, and I’m sure somewhere, deep down, I am. I have no doubt that if I were to improve dramatically next week or next year, I would have a lotof grief to process about time I lost, the experiences I didn’t have. Sometimes I’m afraid I would be overwhelmed by the enormity of it.

But I also, most of the time, really don’t hate my life. I can’t tell how much of that is I’m too tired to imagine doing anything else with it, and so I’m grateful I don’t have to, and how much of it is truly acceptance, peace, and some kind of Herculean (and relatively new to me) ability to find joy and meaning where I can, within the confines of my small little life - in fact, maybe even because of the confines of my small little life.

You see, as always, i reject the notion that everything happens for a reason or that illness is a gift or a lesson blah blah blah.

But I also can’t deny that there’s a certain fairytale logic, a certain narrative symmetry, in what has happened to me.

Our young heroine, wracked with anxiety and FOMO and over-achiever perfectionism who could never slow down, could never stop moving, could never give herself a break, knowing her only two speeds were rigid anorexic perfectionism (but no life) or a compulsion to do ALL the life (but descend into self-destructive chaos and underachievement), who felt the full pressure of life bearing down on her at all times, as though every aspect of living was a fast moving train she was compelled by some punishing force to try to jump or finagle her way onto, after which she was then destined to jump, dangerously, from train to train to train to train for years and years and decades and decades.

That girl, driven but so miserable she sometimes wanted to die just to make it stop. And then… she is stopped. She is given a kind of death. A living death. Where she cannot hop the trains, she has to stop caring about trains, she can hardly remember the trains. She can’t do anything else either, but who cares? She doesn’t have to rally. She doesn’t have to fake it. She doesn’t have to fail, and disappoint everyone everywhere all the time.

In this story, it is like one of those fables where someone makes a wish but wasn’t “careful what they wished for.”

“I want it all to stop,” she wished. And so it did.

And while this isn’t quite what she - what I - meant, I can’t say I don’t appreciate the quiet.

Not that it is all quiet, of course. Some people think being homebound and bedbound is like a vacation - like every day is a lazy Sunday, all crossword puzzles and late brunch and catching up on prestige TV.

And let me tell you, it is not. This type of disability is more like… well, imagine what would get you to call in sick to work, to stay home from school as a kid, to take yourself to the ER. Imagine how bad you’d have to feel.

You might spend your day shivering with chills and sweating with fever. Curled up on the bathroom floor waiting to puke. Crying from stomach cramps. Weakly sipping broth in front of daytime TV before dozing off into a medicated sleep haunted by hypnagogic hallucinations. Your day would be dictated by symptoms, and managing those symptoms, and trying to find any sliver of comfort.

But also, there would be the nice things. The novelty of getting to sleep on the couch instead of in your bed. The comfort of your mom or partner putting a cool washcloth on your forehead or rubbing your feet. Getting to consume trashy TV or magazines because your brain can’t handle anything more complicated or higher stakes. And those moments, when you feel a little better for awhile, or you’re starting to improve but you’re not tip-top yet, where you live in a kind of limbo state, still too sick to go back to your life but well enough to appreciate the little things - the crisp fizz of chilled Sprite, the soothing slushy cold of a milkshake sucked through a straw, the warm glow of your loved ones’ company, and also a brief respite from all the things you can’t do so you don’t have to feel like you should be doing them: bills, taxes, emails, events, anything.

And that, I suppose, is where I find myself now. Swinging between the sick state that is only misery, and that limbo state that still sucks but also has sweetness within it, and some of that sweetness is because of the limbo state. Because it is outside the pace and hustle and expectations of regular life.

Though I have also recently realized two things about this state I’m in.

First, it is not nearly as outside the “pace and hustle and expectations of regular life” as you would think - or I have thought.

This isn’t entirely new information to me. I have long known that I have the ability to expand or shrink my To Do list and sense of pressure, obligation, and urgency, Alice-in-Wonderland-style, to fit my level of function and capacity so that what I want or need to do is always just beyond what I can do, so that, no matter how big or small my life is, or big or small my amount of energy, I can never ever feel “on top of it,” can never relax into the ease of sustainable flow and balance, can never escape the feeling that i “should” be doing something other than what I’m doing, that I’m falling behind.

And what’s more, no matter how many responsibilities are out of my reach and taken on by other people or simply abandoned, the business of being chronically ill is still a full-time job. Yes, there are the literally dozens of pills to be sorted and taken on schedules and re-ordered and pre-authorized; the treatments to try and track; the appointments to make and attend and then process and log; the test results to track down; the government programs to apply for and stay on top of; so many forms to fill out and questionnaires to answer; so many symptoms and data points to capture and analyze; so much medical equipment to buy and unpackage and set up and clean.

But there is also the business of taking care of myself, which, when you’re this sick, is itself quite a lot of work. Brushing my teeth is an exhausting chore and frankly, I don’t manage it every day. Washing my hair takes days of planning and recovery. Feeding myself, doing dishes, changing sheets, getting dressed or undressed… these “little” tasks are my job now, requiring a comparatively similar effort and taking a similar toll as, say, manual labor. Like if every day all day you had to do the equivalent of build a fence or paint a house or replace the transmission in a car, just to keep yourself alive and not living in squalor - ON TOP of your regular job - except you also had to do that with the flu and a broken arm.

So, all that I already knew.

But I recently started taking a course geared towards healing and recovery from ME/CFS, that focuses in part on nervous system regulation and deep, restorative rest. And as I have begun to catch myself every time I have a feeling of urgency or start ruminating on everything I “should do,” or bracing or tensing my body as though ready to spring into action, and as I have begun using exercises throughout the day to restore my nervous system’s equilibrium (and not just waiting for somatic therapy every other Friday), and to take long breaks to meditate or listen to audiobooks at regular intervals instead of waiting until I feel like absolute ass and then taking a reluctant, resentful, and begrudging nap, and as all of that has brought me into a more frequent state that feels something like calm, peace, and even dare I say it, joy, I am realizing how many day of these last eight years I have not been resting. Not at all.

Even as I’ve been lying motionless in bed, watching 700 hours of Love Island, looking like I’m resting, I have been agonizing. Efforting. Worrying. Hoping this next nap will be the one that gets me back on my feet enough to answer that text message or open that pile of mail. Denying myself the pleasure or peace of just sitting outside and watching the trees in the wind because I don’t “deserve” pleasure until I have finished everything I need to do (which of course will be never).

Even in my sleep, my jaw is clenched, my hands balled up in fists, tense.Here I am, stuck in my house, almost no one to answer to and nothing to answer for, compared to my old life, and I am still stressed the fuck out.

It turns out that, just because it has been years since I felt the newly-much-sicker-and-living-with-my-parents despair and hopelessness that made me long for death, just because I now like my house and friends and how I spend much of my time and no longer ache for something different, just because I am not in constant existential agony, that all doesn’t mean that I’m not also still torturing myself all the time, and doesn’t mean that I’ve actually been fully living, either, which, for me, in this state, would mean resting. TRULY resting. In body and in mind.

So, there’s that.

And then there’s the second thing I have realized.

It too is something I’ve known, on some level, for a long time. But it wasn’t until therapy with my OCD specialist last week, sitting in my gravity chair with a view of the pepper tree outside, my therapist’s face on the screen of my computer - the only way I’ve ever seen her - that the full weight of it really sunk in for me:

I am afraid to get well.

Now, before all you Law of Attraction types get excited and say “I told you so” about all those times you said I was sick because I wanted to be sick, that I wouldn’t get well until I wanted to be well, that I have manifested this all and I can manifest my way out of it: pipe down. That is not what I mean, and that is not what’s happening here.

I have a very real physical illness, made possible because of a combination of genetics and trauma and external circumstances that lined up the dynamite and laid out a fuse, so that when the one-two punch of the emotional trauma of my dad’s death and the physical trauma of a viral infection hit me within days of each other (also no coincidence) lit that fuse, my body was ready to blow.

I did not “think” or “believe” my way into getting sick, nor did I “think” or “believe” my way into getting worse. In fact, the year that I did the most “believing” I could get better was the year I landed in bed for good.

AND YET. ALSO.

Part of the mechanism of this disease is nervous system dysregulation. And it is hard to be regulated while also carrying deep fear and doubt. What’s more, there is no way that fearing wellness serves me, whether I get better or not. Like, if I were cured tomorrow, I would need to face that fear in order to, you know, live.

And if I weren’t… actually, that is the way it serves me. In a way, the fear protects me. Because if a part of me feels like my life is better sick than it was and would be well, then I don’t have to grieve what I can’t do, I don’t have to feel sad about how small my life really is. I can be happy and grateful for the escape, instead of angst-ridden over my imprisonment.

And that is there, it’s true. I am afraid to not be afraid of getting well, because of what I might find and feel in the stark light of that reality.

But that’s not all it is.

It is that I can’t imagine a life where I am not this sick, where I am not also even more miserable.

It is that I have never been well.

Many people with ME/CFS or Long Covid fantasize about returning to the life they had before they got sick, when they had boundless energy and agency and something like success, whatever that means to them.

But I don’t really remember a “before.”

I have had severe anxiety for as long as I can remember. In second grade, I would stay up and read until 4am, propelled by some nameless internal motor that made me afraid to sleep. In fourth grade, I was so anxious I couldn’t even sit still to watch a movie - I had to be doing something “productive” too, like watching “Dirty Dancing” and organizing my files (and yes, in fourth grade, I had files).

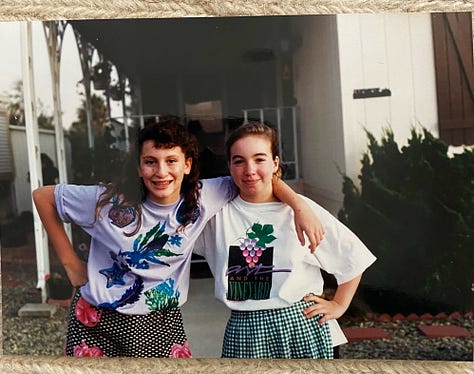

In junior high, this turned into an eating disorder and a punishing need to take dance classes 24 hours a week. In high school, it morphed into an unhealthy desperate obsession and fear around my social life, to the detriment of my grades, and smoking and drinking to self-medicate.

I was already struggling with intense fatigue at 15, two years before the hammer really fell. I took a full-sized thermos of coffee to school, and popped No-Doz and Vivarin like Tic Tacs, and I would still fall asleep in fifth period Bio every day.

And then, at 17, I got sick sick, and it never let up - and, in fact, just got gradually and almost imperceptibly worse for the next 30 years.

Every year of my life that I can remember, it has been hard. Even in my best moments - falling in love with Portland and with college, falling in love with several boys (and a couple girls too, though neither of us called it that), getting my first journalism job, starting my dance troupe in San Francisco - I was also exhausted, miserable, and on the verge of completely falling apart. And not infrequently, I did fall apart.

I lost multiple jobs because I couldn’t handle the schedule of maintaining several social circles, the self-medication that made me feel better in the moment but worse in the morning, and the actual 40-hour work week which, all by itself, even without that other stuff, was too much for my body.

My car was repossessed because I was too fatigued to reliably move it for street-cleaning, and too cognitively exhausted to make a different long-term plan for parking, and so I spent all my car payment money on impound fees and parking tickets instead of, well, car payments.

I lost rooms in several houses for similar reasons.

For decades, I only ever had the energy to handle the responsibility, or the need, or, most often, the emotional or physical urge or imperative, immediately before me. No higher perspective. No goal setting. No planning. I was the cartoon of the guy plugging holes in the dyke with a finger, only for another hole to open up next to it, until every appendage is plugging a leak. When all your fingers and toes are stuffed into holes to prevent imminent disaster, it’s really hard to think about how maybe you should rebuild this fucking dyke - or maybe move somewhere that doesn’t require one.

Honestly, it’s a miracle I’ve done as much, or done as well, as I have, all things considered.

If my bosses at my last newspaper knew how hard I was struggling even when I took that job, none of us would be disappointed they had to ask me to leave after three years - we’d all be impressed I even made it that long. Same for my bosses at the paper before that. And the one before that.

If anyone really knew how hard I was trying. How desperate I was to find answers (what did you think all those communes were for, mmm?). How wracked with fear, shame, guilt, and confusion. How very very very physically and psychologically and emotionally tired. If anyone knew, they’d give me a medal. Or maybe a sandwich and a warm bed and then like 8 years of therapy and naps.

Which, well… * jazz hands *

So when I imagine suddenly (or even slowly) having the ability to work, to socialize, to drive further than 20 minutes, to sit up longer than hour, the only thing I can imagine is that I would then be forced to return to the life I had before, the way it was before.Napping on low pile carpets in the corners of office buildings on breaks. Crossing my fingers that this lease I’m signing I won’t have to break. Drinking to blackout to numb out my symptoms so I can keep up with my friends at the party.

I have no other point of reference.

The last time I remember being unbothered, moisturized, happy, in my lane, and focused, my parents weren’t yet divorced. Which means I was four.

Now, of course, intellectually I know that I am a different person than I was eight years ago. Not only have I been forged into someone new by the fires of disability (specifically disability in America), reborn after visiting the underworld again and again. But I have also been in a shit ton of therapy. Multiple types of therapy. For almost six of those eight years.

Once I stopped moving, and learned to ask for help, and fell so low we all were scared for my well-being, I finally had the time and motivation and interest and resources to deal with all the holes in the dyke - and then the dyke itself - and then the land on which the dyke was built.

They say it takes seven years for the cells in your body to regenerate completely, making you a different person every seven years, and I feel like I’ve been doing something similar with my neural pathways and my deep inner pain. Gradually replacing each maladaptive pattern or self-defeating thought or subconscious fear with something healthier and more self-supportive, more life-affirming, until I almost do feel like a completely different person than I was when I started.

And so I know that if I were to find myself out in the world again - at a job, at a dinner party, on a road trip, at Burning Man (if I even want to go anymore) - I would be approaching it with completely new perspective and different tools.

And also, by definition, I would feel better than I did. If the fantasy is that I’m suddenly cured, then I would be cured. The fatigue, the need for naps every three hours, the brain fog, the headaches, the predisposition to dehydration… all of that would no longer be a factor either, no longer making me miserable everywhere I go.

I know that.

In my brain.

But somewhere, my body doesn’t. It’s like trying to convince myself that it would be safe to walk on the moon. They tell me it’s true, and I’ve seen other people done it, but I’ve never been in space, and I haven’t even been trained in simulations, and I just cannot imagine that it is possible for me.

And so, when I think about these eight years, and what else I could have been doing, what I think about is where else I could have been miserable, and not making enough money, and bailing on plans with friends, and ending up in situations where my boundaries and my body are violated (by me or others), and I am so gratefulI am not and have not been there.As much as I miss my friends. As much as I miss the parts of my life - even during that time - that were amazing and fulfilling and joyful.

But upon this eight year anniversary, I have chosen to take a look at both of these revelations. At the fact that I still have not rested. And the fact that I am afraid to not be sick.

And I have decided to do something about them both.

As part of the program I’m in, I have begun prioritizing my peace and my joy and listening to my body above all else (you’d really think I would’ve done that before, but you wouldn’t believe how hard it is to actually do until you’ve been chronically ill, or how much you can think you’re already doing it when you aren’t).

And so that, finally, is leading me to rest.

As for revelation number two… in therapy, we are going straight toward the fear. To tease it out, unravel it, and see how we can transform it.

I have no idea if either of these things will lead to progress in my illness. Obviously I hope so. I always have hope that something will change or improve, even while the other side of the scale is balanced with acceptance of the possibility it will always be like this (or worse), and faith I will be able to handle that too. But with chronic illness, you just never know.

What I do know is that neither of these strategies will make me worse. And that my situation is unlikely to improve without addressing them both. And that, even if not one physical symptom changes, facing both will reduce my suffering, and make this already surprisingly livable life even more so.

(And again, when I say surprisingly livable, I don’t in any way want to downplay how hard and miserable it is to be chronically ill. How lonely. How scary. How much pain I’m in all the time. I just mean that in spite of all that, I don’t actually hate my life, and that is quite a remarkable thing.)

And so, here I am, starting Year Nine. The year I will turn 47. Riding in this car that is either careening, or sputtering - depending on which kind of time traveler I am at the moment - towards a moment in the future I might be able to say I spent my entire 40s lying down. Or that I narrowly escaped that fate. I don’t know which.

And I have no idea how this year will map onto the timeline. If it will fade into other years, or be distinct in its character and events. (Though what’s happening in the outside world seems to suggest it’ll be the latter, no matter what I personally do.)

The craniosacral therapist told me that I should try to move my body more. She’s not like the dozens of doctors who don’t understand my disease or my limits and have told me to take up swimming, or that if I don’t walk two miles a day I’ll lose my colon. She gets that exertion is dangerous for me. But she also gets that so is too much stagnation.

“Even if it’s just stretching in your bed,” she said. “Even if it’s just pointing and flexing your toes. Whatever feels good in your body. Something small can make a big difference.”

And my intuition tells me she’s right. I need movement. Literally and metaphorically. I am ready for change, even if I don’t know what change will look like.

And so I don’t know what this next year will bring.

But what I do know is that I am going into it boldly, but also gently, tenderly. Open and with curiosity, with deep listening for what feels good, and deep love for that little (and older, and even older still) girl who has struggled so much for so much of her life.

Whatever happens next, I hope it brings her peace.

I hope it brings her safety.

I hope it brings her rest.

This is one of the best explanations of ME/CFS I’ve seen. Really really well done.

I was one of the lucky ones who came across the right information on social media and gave myself the stability (physically, mentally, spiritually) I needed to let my body recover. Even so, it’s taken a year to feel “like myself” again- aka not severe. I know I still have to be mindful.

There’s really no way to recommend an energy healer to a stranger on the internet without sounding ridiculously spammy, but my friend Luna is remote and has helped me work through so much of the grief and fear you mentioned. Please, please don’t hesitate to reach out if you ever want her contact.

Wishing you peace, safety, and real rest. ❤️

Wow. This is incredibly insightful. And sounds a lot like Mel Abbott’s journey from bed for 15 years to recovery. It also sounds like the work you’re doing is very much aligned with hers. If you want to check her out, she’s here: https://empowertherapies.co.nz/