What IS ME/CFS anyway?

Resources for explaining our illness to friends, family, allies, doctors, and that one guy who keeps telling you to drink butter coffee

Last week marked the end of my sister’s extended trip to visit me (if Muhammad can’t come to the beach, the beach comes to Muhammad), and while the extra time together was glorious, I have spent the days since she left battling one of my signature monster headaches - the kind that pulses behind my left brow and both temples and the points just above my jaw joint and the base of my skull and along the side muscles that hold up my neck, while also swelling the glands in my throat and making me seasick. Fun times!

For this reason, I’ve struggled to write something poetic and deep, or long and thoughtful, but it turns out, that’s actually perfect timing. May is ME/CFS Awareness Month, and so me having a flare that gets in the way of my plans and my work and my life is RIGHT ON THEME. (No idea at all what ME/CFS is and want to get right to it? Check out this footnote1.)

This, my friends, is ME/CFS! Wanting to give the world a beautiful essay, and being given a nasty head-pounding instead. A life of annoying, unfunny switcheroos.

The good news is, I already started compiling ME/CFS content back when I started my list of ableism resources, and was waiting for the right time to share them. And what better time than now? So beautiful essay you may not get, but beautiful resources? Still in the cards.

But first. A preamble.

In this month of ME/CFS awareness, I ask you:

How aware are you of ME/CFS?

What do you know about it?

When did you first hear about it?

When did you last hear about it, from someone/somewhere other than me?

I’m guessing that unless you have ME/CFS yourself, or someone very close to you does, you probably don’t know much about ME/CFS. And I’m willing to bet you almost never hear anyone mention it. Not in your life. Not on social media. Not on TV. Nowhere.

That might not seem strange, considering there are more than 26,000 known diseases and no one person can know about all of them. Until you think about how many diseases we do know about, how common ME/CFS actually is, and how completely it devastates the people who live with it.

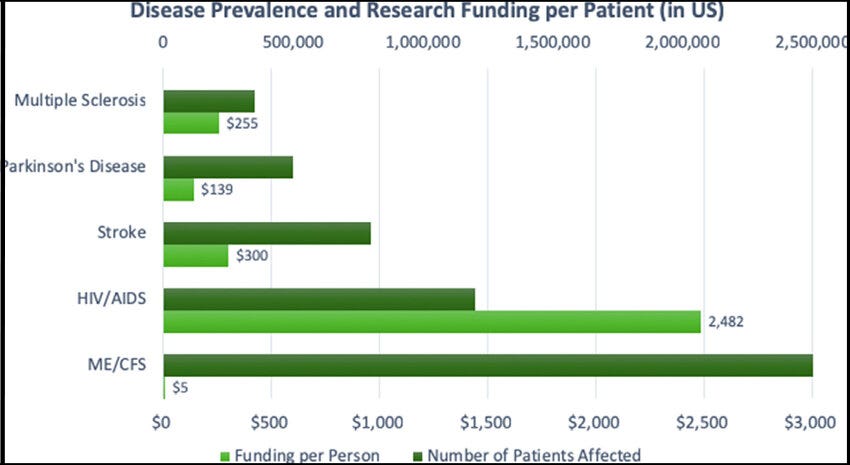

More people in America have ME/CFS (4 million2) than have HIV/AIDS (1.2 million), MS (1 million), Parkinson’s (500,000), or ALS (30,000). And the disease is considered more debilitating than MS, congestive heart failure, and stroke, with a quality of life on par with someone with late stage cancer.

And yet, not only is there no ME/CFS Ice Bucket challenge, no special ME/CFS episode on Grey’s Anatomy, and no tear-jerker romcom with a manic pixie dream girl suffering from ME/CFS, but not even our doctors know more than the most basic thing about it. And our friends, when told our diagnosis, meet us with blank stares. Usually anything they know about our disease they hear from us, or, very rarely, look up themselves because of us.

Despite it being so prevalent, and so devastating, ME/CFS is one of the least acknowledged, least understood, and lowest funded (about $5/person with ME/CFS compared to $255/person with MS), neurological diseases in our country.

So… why?

It’s complicated.

Many of the reasons are outlined in the amazing memoir, “The Lady’s Handbook for her Mysterious Illness,” by Sarah Ramey. But they can be boiled down to a couple key reasons:

Bad branding. Though ME/CFS has been around for hundreds of years, or longer, (did you know Charles Darwin, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and Florence Nightingale are all thought to have had it?), it was dubbed “Chronic Fatigue Syndrome” in 1988 - a name that vastly understates the severity, and the multi-system symptomology, of the disease, and made it easy to ridicule and dismiss as the “yuppie flu.” Just imagine the phrase “Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.” What do you see in your mind? Is it someone in a dark room, face twisting in agony at the slightest sound, being fed with a tube, afraid to lift an arm for a drink of water because doing so could trigger a symptom flare that will last hours or days? I didn’t think so. And that’s part of the problem. (And yes, that is what the more severe end of the illness looks like. That’s not hyperbole. And if you’re curious, that’s considered a 0-10 on a 100 point illness skill. Where I sit is somewhere around 20-30 - so not as far away from that as you’d think.)

Misogyny. ME/CFS affects women more than men at a rate of 4 to 1. And science (and society) cares, funds, and believes women (and other non-men) less than they do men. In fact, for hundreds of years, ME/CFS was dismissed as “hysteria.” If men were complaining of cognitive impairment, musculoskeletal pain, headaches, intense fatigue, unexplained flu symptoms, and an inability to tolerate more than 12 foods, the whole world would be talking about it and trying to solve the puzzle. Which… now that there are so many people with Long COVID that even the tiny fraction of them that are men adds up to a lot men, at least that convo is starting to happen. (Though science is still slow to connect Long COVID and ME/CFS, which is what nearly all Long COVID cases that last longer than six months become. But I digress…) But until now, since it’s mostly been women in male doctor’s offices complaining of multiple seemingly unrelated symptoms, they’ve been sent home with meds for depression or anxiety, and been branded in their charts as hypochondriacs, all while their friends and family at home dismiss them as lazy, whiny, overly sensitive, or (my personal favorite) unwilling to face their trauma and committed subconsciously to not being well. (Sidenote: imagine the audacity of saying that to someone who came home with Huntington’s Disease or a traumatic brain injury).

It’s invisible. We love an illness we can see. Michael J. Fox with his tremors. Tom Hanks wasting away in Philadelphia. Teddi Mellencamp with her chemo buzz cut. But ME/CFS doesn’t have any of that, except in the most extreme cases and on our most extreme days. Most of the time, we look like perfectly healthy people, because you can’t see a migraine, or painful bouts of IBS, or the feeling of your arms being made out of lead. And when you can see it on our faces - a drawn look, droopy eyes, face long, skin grey and seeming to sag - usually you can’t see us, because we’re too sick to leave our rooms. Our symptoms are invisible but also we are invisible, because the sicker we are, the less we can be in society. And it’s hard to connect to, or feel sorry for, or even remember the existence of, someone who’s alone in their house in a dark room, for days and weeks and months and years.

It’s boring. We love an illness we can see, and like it or not, we also love an illness with D-R-A-M-A. One with obvious symptoms, a heartbreaking decline, and a tragic ending. But ME/CFS is none of that. Our symptoms are stealth. We do decline, but that usually happens slowly and invisibly too (how do you depict the gradual loss of the ability to digest food in an exciting way?). And annoyingly (to narrative plot structure and, honestly, to many of us), we do not usually die. Though our mortality rate is very high, the majority of those deaths are by suicide. (Very severe ME/CFS can be fatal, usually via organ failure, but those deaths are rare.) It is not the disease itself that kills us, what kills us is the pain of having to live with this much misery, and in a society that isn’t trying to accommodate, protect, or help you, day after day. But that’s not as sexy or exciting. And because our culture still stigmatizes mental illness and suicide as personal or moral failings, no one is taking seriously what it means that so many people would rather take their life than live one more day with this illness. The very chronic-ness of the illness, the mundanity of it, the endless laying in bed in pain without hope of a cure, is what makes it so terrible - and also so… tedious, unentertaining, and uninspiring.

And yet, despite all of that, it is important that people know about ME/CFS. It’s important because people like me deserve to be seen and understood by the people they love. It’s important because doctors and medical professionals should learn how to treat us. It’s important because researchers need to be doing studies, funders funding those studies, and the government protecting our services - and those studies.

And it’s important because more people develop ME/CFS every day. It was already more prevalent than you think before 2020, but our numbers have ballooned since the start of COVID. Since ME/CFS is often a post-viral illness, and COVID is a virus that has been left to run rampant and re-infect people over and over, there are now 20 million people in the U.S. who have been diagnosed with long COVID, 1 million of whom now meet the criteria for ME/CFS. And counting. This mass disabling event is nowhere near over, and it’s possible at some point in the near future, everyone in America could either have long COVID or ME/CFS or know someone close to them who does.

When that happens to you or someone you love, I’d like the people around you to know what you’re talking about, and have the slightest idea of what you’re going through.

And so. We have this month for spreading awareness, and that’s what I’m going to try to do. My personal mission is to help ME/CFS become a household word in my lifetime.

I want the average person to be as familiar with it as they are with diabetes, arthritis, and COPD. I want celebs who have it (Cher, Stevie Nicks, Flea, likely Justin Bieber) to claim it, claim us, and speak out. And I want that awareness to translate into research funding commensurate with the number of people who suffer from it.

Which starts with learning what it is. Hence, the resources I’ve compiled below.

If you’d like to help me achieve my mission, please do one or more of the following:

Read or watch at least one of the resources below, and comment here (or on that video or reel) something you learned, found interesting, were surprised by, or have a question about. Personally, I love questions, and (almost) nothing is too personal, if asked in a spirit of curiosity and respect.

Share at least one of the following resources on your own social media, or personally, with someone you know (especially if that person is a medical student or medical professional, is in politics, or is in media/public relations).

Participate in Millions Missing on May 12, by watching and re-sharing content by me and by ME Action, by attending the protest in D.C., or by making your own content (a toolkit is here, organized by amount of spoons it would require to do each action).

If you have made it this far, thank you. I am touched, and I’m honored. This issue is so close to my heart, and is so very very personal. One of the ways I feel most seen is when people learn and care about the illness that has completely defined and up-ended my life for the last eight years (but really, the last 32). And if me being one of the people served this particular shit sandwich can somehow lead to helping others around the world who are also eating this shit sandwich, that will add just a little more meaning to a life where sometimes meaning is hard to come by.

So for whatever you can do, and already have done, thank you. I love you. Now I’m going back to bed.

Resources

What is ME/CFS: for friends and family (Video, 6 min)

This stop motion animation with watercolor props gives an overview of what ME/CFS is and what it feels like to have it, including the emotional impact of having such strict limits. Geared towards friends and family, it gives advice for people who love us (spoiler: try to understand our new reality and meet us where we are). Informative, simple, and pretty to look at.

ME/CFS in Real Time: What’s happening when you hang with us (Video, 3 min)

This award-winning short documentary gives a visceral description of what it’s like to have fatigue, sensory sensitivity, and cognitive dysfunction in the moment, including the moment the switch flips and you’re suddenly running on adrenaline. A good resource to show people who have spent time with you and perhaps notice you losing words, or suddenly getting chatty after being sluggish.

ME/CFS, Spoon Theory, and what a crash feels like: If you only watch one video, watch this one (Video, 9 min)

This video might be one of the best descriptions of ME/CFS I’ve seen, in terms of showing what the reality of dynamic illness (meaning symptoms change from day to day) looks like, what crashes feel like, and how pacing works (and how it affects your life). If I had to choose just one thing to show to someone who knew nothing about ME/CFS, it’s possible this might be the one I’d choose.

Unrest: the award-winning documentary (Movie, 97 min)

Unrest, the full-length documentary by ME/CFS celebrity Jen Brea, has become the gold standard of ME/CFS media. It is an imperfect documentary for truly explaining the illness to someone who knows nothing about it, as it doesn’t spend much time describing the illness, the process of diagnosis, or its various treatments. The purpose of the documentary is to make a case for why ME/CFS deserves funding, and so the movie focuses on the experience of those with the illness, how serious their symptoms are, how poor their quality of life, and how profoundly ignored and misunderstood they are by doctors, the healthcare system, and often even their own families.

I hesitate to give this to peopl as the only resource explaining ME/CFS, but the reason I do give it to people is that I have never seen anything that so clearly depicts the emotional experience of having this illness, including the devastating despair, depression, loneliness, isolation, and fear. You may not come out of this knowing the words for my co-morbid conditions, you’ll have an understanding of my inner emotional life and journey that you didn’t before. When my best friend watched it, she cried - and that is exactly the kind of validating response this movie was made for.

(Also of note: after making this film, Jen discovered that a primary trigger for her ME/CFS was structural issues like craniocervical instabiliy and tethered cord syndrome, so she exhibits a lot of neurological symptoms that aren’t typical in all of us. However, more and more of us are discovering we have structural issues too, and pursuing that diagnosis and treating any abnormalities has become a major (and controversial) breakthrough in the past few years. But if you don’t exactly see me or your sister or friend in all of Jen’s symptoms, that’s likely why - she had a lot more brain stuff going on than many of us do.)

TED Talk: Jen Brea (Video, 17 min)

In this 17-minute TED Talk, Jen Brea tells her story and covers some of the themes in her documentary in an easier to digest format (while also mirroring disability accommodations for dynamic disabilities while doing the talk in a wheelchair, taking speaking breaks, and asking the audience to snap instead of clap). Here she describes how hard it is to be diagnosed with an invisible chronic illness, how the way we talk about invisible illness is the updated (sexist) form of what used to be called “hysteria,” and how we need to take patients seriously.

Again, this talk’s purpose is more advocacy than education, but it does educate about ME/CFS in the broader context of society, healthcare, and history (as well as give some details about the illness itself, and the nearly universal experience of trying to be diagnosed and being dismissed and ignored).

The Medical Perspective (Video, 12 min)

If you want something more technical and medical, watch this 12-minute video by my (and Jen Brea’s) former doctor, Dr. David Lyons Kaufman, an infectious disease specialist who came up during the AIDS crisis and now applies what he learned there to our not dissimilarly complex and under-funded/under-researched disease. Geared towards other doctors and made as part of a former Continuing Medical Education (CME) course (classes that count towards the 50 hours of education required for the biennial medical license renewal process), this video talks about the specifics of disease triggers, symptoms, diagnostic tests, and management tools and medications. This is a great place to start if you really want to understand the details of the illness, and especially if you are going to work with people with ME/CFS in any wellness capacity (eg with body work, plant medicine, healing modalities, alternative medicine, yoga, etc) or are tempted to start suggesting treatments to someone with ME/CFS.

What I’m Missing: A Reel from Moi (Reel, 5 min)

I made this video as part of the 2023 ME Action Millions Missing campaign. The idea was to tell a little bit of our illness/diagnosis story, and then explain what it is that we’re missing in our lives (and why we’re missing from yours) because the government underfunds research for our illness (and refuses to protect us from getting worse, or others from getting our disease, by taking the pandemic seriously). You can also read the text in the caption (note: half is in the comments) if you click through. And yes, I know this thumbnail is very unflattering. No, I don’t know how to change it lol.

Monthlong Series on ME/CFS Topics (Reels, multiple lengths)

Anj Granieri, an artist who is in remission from severe ME/CFS (a feat that is rare but not impossible, and most common if the disease is caught in the first five years - though I have found some improvement from working with her, so who knows???), is making a series of videos about ME/CFS for every day of this month. The one below is the first in the series, explaining the basics of ME/CFS, but please do check out her page and watch and post her subsequent videos on everything from exercise intolerance to misdiagnosis. She is a smart, passionate, compassionate person with a flair for explaining complex concepts, and the work she’s doing is important.

The Very Basics of Long COVID and ME/CFS (Article, 4 min read)

If you’d rather read than watch, this article is a good overview of the basics of ME/CFS, long COVID, and how they’re related.

A quick preview, summarized by yours truly: ME/CFS stands for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, and refers to a neuroimmune condition whose cause and cure are unknown, and mechanisms are not well understood, but which manifests as dysfunction in nearly every system of the body, and with hallmark symptoms of intense fatigue, an extreme increase in symptoms after any kind of exertion, cognitive dysfunction, under- or over-active immune systems, and trouble regulating the autonomic nervous system. 70% of people with ME/CFS can’t work, and 25% are bedbound. At its mildest, people with ME/CFS have 50% of the function they had pre-illness. Read that again. Losing HALF YOUR LIFE is what we consider MILD. Though we don’t know what causes ME/CFS, we do know what triggers it - as in, there are certain factors that create conditions for illness to take hold, like genetics, chemical exposure, surgeries, childhood illnesses, childhood trauma, etc. And then there is something that pushes the body over the edge into full blown illness. For ME/CFS, those triggers are viral infections (by far the most common), bacterial infections, traumatic injuries, emotional traumas, a serious mold exposure event, and, again, chemical exposure - like during the Gulf War.)

Most stats say there are 3.3 million people with ME/CFS in the U.S. But it’s also estimated that 1 million people with long COVID also meet criteria for ME/CFS. The 4 million figure includes those with long COVID-related ME/CFS (with some wiggle room).

There is so much here, Molly! I’m saving this to look at some more of this later. Thank you for this detailed and thorough set of resources. I belong to the big subset of Long COVIID people who find ourselves with the same sort of issues, and it’s been a long journey to understand it myself, let alone for others to get their head around it.

Thanks for all your work! Greatly appreciated.

Heather